31

The Catholic Leader, March 22, 2020

www.catholicleader.com.auArchbishop John Bathersby

This is the homily of Archbishop

Mark Coleridge at the solemn

pontifical requiem Mass of

Archbishop John Bathersby at St

Stephen’s Cathedral, on March 16

IT must have been all those moun-

tains he climbed – not Everest per-

haps but certainly Tibrogargan.

Long after everything else seemed to shut

down, his heart kept beating, even though the

Bathersbys were supposed to have weak hearts.

He lingered far longer than we expected;

at one point we thought he’d never die. But

finally in the morning light of Monday, March

9 John Alexius Bathersby, sixth Bishop and fifth

Archbishop of Brisbane, breathed his last in the

eighty-fourth year of his life.

News of his death came as the Bishops of

Queensland were preparing for morning Mass

with the students of the seminary at Banyo.

There was a touching symmetry in this. John

had entered the seminary straight from school in

1954; he had returned as spiritual director years

later; and then as Bishop of Cairns and Arch-

bishop of Brisbane he was responsible for some

of the bigger decisions in the seminary’s history.

Here we were at the place that had so marked

John’s life and, as I said to the seminarians, at a

place where they were more deeply marked by

John Bathersby than they realised.

I first met John way back in the late 1970s

when he was spiritual director of the seminary

and I was a recently ordained priest of Mel-

bourne.

He invited me to come to Brisbane to preach

the Holy Week retreat to the seminarians.

When I met him, I was surprised; I’d expected

something more in the imagined mode of spir-

itual directors – ascetical, solemn, other-worldly.

What I found was something quite different:

an Aussie original and a Queensland classic.

I’d never struck anything quite like it; and

through the years since then my sense of surprise

at John Bathersby has never left me.

He seemed the quintessential little Aussie

battler, but he was in fact – as I came to see more

through the years – a man of high intelligence

and deep spirituality, straight-forward yet decep-

tive, a very accessible character yet with great

distances.

There was even a touch of the mystic about

him.

Another small man called John once wrote

a book called The Ascent of Mount Carmel;

he was also into mountain-climbing, but of the

metaphoric kind.

His book is one of the great classics of Chris-

tian mysticism, and in it he sees the spiritual

life as a kind of mountain-climbing – a long and

winding ascent from darkness towards the glori-

ous light of the summit where, according to the

prophet Isaiah, “the Lord of hosts has prepared

for all peoples a banquet of rich food and finest

wines” (25:6).

That was St John of the Cross, and John Bath-

ersby saw the spiritual life in the same terms.

It was a search, at times a struggle for the great

banquet on the summit of God’s mountain when

all the climbing would be done.

John certainly loved a meal.

After our first encounter at the seminary, we

were together again in Rome in the early 1980s

– he doing a doctorate in spirituality and I the

Masters in biblical studies.

There was quite a group of young Australian

priests studying in Rome at the time, and we’d

meet regularly on a Saturday night for a meal,

eating our way through the menu and drinking a

bit too much wine.

Those meals were one of the more important

and memorable moments of my years in Rome,

and John Bathersby was at the heart of it all,

master of the banquet in a most unpretentious

way.

He was delightful, often hilarious company,

regaling us with stories of extraordinary charac-

ters of the Toowoomba diocese and eye-popping

events from his time in Goondiwindi.

But there was more than the fun. There was a

human solidity and a spiritual depth which were

precious in our time away which most of us

found humanly and spiritually taxing.

He was a bit older than the rest of us and had

a wisdom to match. As I look back now to those

Reaching the end of the climb

years and those meals, I can see that I owe John

Bathersby a deep debt of personal gratitude in

ways that are not easily expressed, at least in a

forum as public as this.

But thanks, Bats, for everything.

Beyond those years in Rome our

lives became more and more

strangely interwoven until

finally I was appointed to

succeed him in Brisbane

after his retirement

in late 2011. When

news of my appoint-

ment came through,

I thought of other

times at Banyo and

in Rome – and how

bizarre it was that I

was to follow him as

Archbishop. I’d never

really thought of John

as the kind of man they’d

appoint to Brisbane, and

I had absolutely no sense

that they would appoint me to

succeed him. I thought of the mo-

ment when, after one of those Roman meals,

John offered to take me home on the back of his

motor-scooter.

The night was wet, the cobbles slippery – and

I clung on for dear life. I’d never been

more relieved to make it home,

and I vowed never again

to ride or go pillion on a

motor-scooter, at least

not with him.

I think now how

extraordinary that

two Archbishops of

Brisbane were on

that Vespa and both

of us could’ve been

killed.

One of the good

things about coming

to Brisbane, I thought,

was the chance to spend

time with John.

But it wasn’t to be. By the

time I arrived the dementia was

already taking hold, and any attempt I

made to pick his brain about the diocese came to

nothing. The blankness was descending.

This became more dramatic as time went by,

to the point where towards the end there was no

recognition, no power of speech.

Knowing what John Bathersby had been in his

prime, the marvellous vitality of the man, there

was more than a touch of tragedy about this.

He had always dreamt of retiring to Stan-

thorpe, perhaps to write some local history. But

that too was beyond him and a move back to

Brisbane was inevitable as the demen-

tia worsened.

In the end his world was

small and simple, but in a

sense it always was. The

younger John had no

episcopal aspirations

or ambitions; and as

Bishop his was never

the grand style.

It took him quite

a while to learn how

to manage a crozier;

he needed the then

Fr Ken Howell to tell

him what to wear and

when; and though he

lived in the big house at

Wynberg his own quarters

could hardly have been humbler.

I took one look at them when

I came and immediately decided to move

upstairs to something more spacious.

Just as Pope Francis is recasting the papal

style, making it less monarchical, less grand

in scale, John Bathersby recast the

episcopal style, making it more

down-to-earth, less princely.

He was more a pastor

than a pontiff.

John had his crises,

perhaps even his

failures, especially

in the later years as

dementia began to

take hold.

But through it all,

in the words of the

Letter to the Hebrews

which he loved and

often quoted, John did

not “lose sight of Jesus”

(12:2).

But perhaps his legacy

is deeper and may prove more

enduring.

Before all else John Bathersby was a lover

of Jesus, and he spoke of this more as he grew

older.

In the Gospel we have heard today, the Greek-

speaking Jews say to Philip and Andrew, “We

want to see Jesus”; and that was what drove

John Bathersby.

He wanted to see Jesus, and that became an

ever deepening passion in his life.

The One he wanted to see was no pale Galile-

an or good old plastic Jesus. It was the crucified

Lord, here and now as presence and power; and

it was no accident that he took as his episcopal

motto Lex crucis, the law of the Cross.

Nor was it by chance that he died clutching a

cross.

There was, he knew, no other way than by the

Cross of Christ that he could reach the summit;

there was no other path. He knew the great truth

spoken by Jesus in the Gospel: “Unless a grain

of wheat falls into the earth and dies it remains

just a single grain; but if it dies it bears much

fruit” (John 12:24). Now the grain falls finally

deep into the earth.

John didn’t speak the language of philosophy

so much; he didn’t specialise in arguments of

intellectual sophistication.

His was the simpler and more mysterious

language of discipleship, and he offered the

arguments of love.

For twenty years he never ceased to point his

flock in that direction, urging them not to “lose

sight of Jesus” in the midst of all the troubles

and turmoil, all the complexities and confusion.

In that sense, John Bathersby was a simple

man, but it was the hard-won simplicity of a man

who had come to know what really mattered

on the long climb of life. That simplicity, that

clarity of vision, is his greatest legacy to the

Archdiocese of Brisbane.

In the Gospel story of the Transfiguration,

which the Church read on the Sunday John lay

dying, Jesus leads Peter, James and John up a

high mountain, and there on the summit he is

transfigured dazzlingly in their presence.

They see him as never before; they see him as

he really is.

Through the years, Jesus has led our John up a

high mountain, and from the summit the view is

spectacular – not the sweeping panorama but the

vision of Jesus. Now that he has reached the end

of the climb, during which he has never “lost

sight of Jesus”, John stands before the dazzling

vision of Christ crucified and risen, the Lord

whose scars shine like the sun.

The climbing is all done, the time for rest has

come, as the Lord of hosts ushers John to the

table of heaven’s banquet where he will surely

be the best of companions as he was all those

years ago in Rome.

Eternal rest give to John, O Lord, and let

perpetual light shine upon him. May he rest in

peace. Amen.

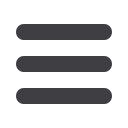

Man of God:

Archbishop Mark Coleridge sprinkles the coffin of Archbishop Emeritus John Bathersby with Holy Water before it is lowered into its

final resting place in the crypt of St Stephen’s Cathedral. Below, Archbishop Bathersby while he was Archbishop of Brisbane.

Photo: Alan Edgecomb