15

The Catholic Leader, April 21, 2019

www.catholicleader.com.auNews

JUST as we have been remembering

the horrors of Rwanda 25 years ago,

another anniversary passed almost

unnoticed this month – the 20th an-

niversary of a Church massacre on

Australia’s doorstep, in East Timor.

In April 1999, five months before East Ti-

mor’s vote for independence, dozens of people

were killed inside a priest’s house and church

courtyard in the idyllic coastal town of Liquisa.

The figure could have been much higher – up

to 200 people – the remnants of a crowd of about

2000 who had attended a morning church gather-

ing on April 5.

At that time I was the ABC’s Indonesia cor-

respondent, and I had found myself travelling

almost constantly between East Timor and my

base in Jakarta.

Only days before, I had interviewed the chief

of one of East Timor’s feared militia gangs – the

Besi Merah Putih (the red and white iron).

He had vowed that “fire and blood” was soon

to be unleashed on anyone who opposed Indone-

sian rule in East Timor.

His prediction of terror was coming true.

I stood in the APTN new agency office in Ja-

karta watching video footage that had just been

satellite-fed from East Timor.

I stood aghast at what I saw – a boy lying on

his side on a white, tiled floor, his back to the

camera, with a deep, long gash down the side of

his body – the signature of a machete.

There was a pool of blood and he was gasping

for breath, barely alive.

Several injured and hysterical people huddled

around.

We were watching the aftermath of a mas-

sacre, and within a day I found myself back in

Liquisa with ABC cameraman David Anderson

trying to piece together what had happened.

We found Liquisa deadly silent – no traffic, no

one in the markets or on the streets.

We headed for the church São João de Brito.

I won’t describe the horror of what we saw in

the courtyard, even though attempts had been

made to wash it clean.

In the nearby house of the priest, Father

Rafael dos Santos had been ransacked, and we

found the floor in one room – the white tiled

floor from the video – covered in blood.

We learned that the priest had escaped with

others to Dili.

However Carmelite Sister Maria Immanuella

had stayed to try and calm emotions.

Nevertheless, I found her overcome by the

horror of what had happened.

“I don’t know how many were killed,” she

said

“According to Fr Rafael seven were killed in

his house. The situation here is tense. Everyone

is afraid.”

I began searching for witnesses.

Nobody in the town was willing to be inter-

viewed for a TV report, so I took notes that I

would use to file a report for ABC radio.

Here are the notes I took:

“About midday a group of up to 500 armed

pro-Indonesia paramilitary – members of the

Besi Merah Putih (red and white iron) – chased

residents of Liquisa to their church. The militia-

men stood outside shouting threats. There were

also Indonesian troops present.

“They stood behind the militiamen outside the

church grounds, and as the tensions increased

they fired warning shots into the air – but

significantly they made no attempt to stop what

happened next.

“An old man who had been inside the church

told me that people around him panicked when

they heard the sound of gunshots.

“Some ran outside into the churchyard. Others

ran to the priest’s house. It was then that militia-

men attacked with machetes. He said people got

their throats cut. Soldiers fired tear gas into the

priest’s house to drive out those who had sought

refuge. One witness said he saw blood dripping

from the ceiling.”

Timor massacre remembered

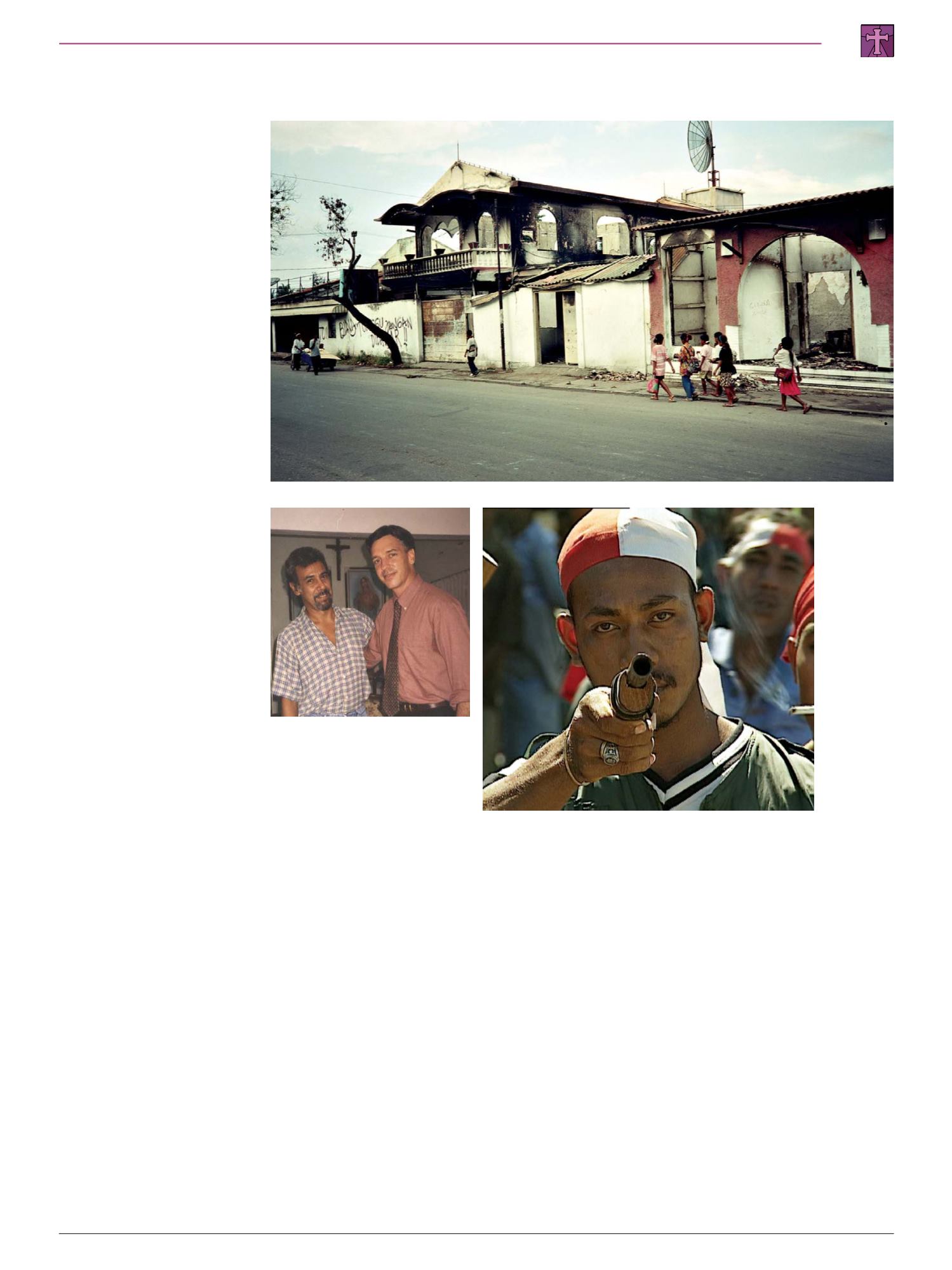

Violence:

A

pro-Indonesia

militia member

brandishing a

home-made

gun. A “red

and white”

civilian army

inflicted

violence and

murder before

and after East

Timor’s vote

for independ-

ence in 1999.

Later, when I entered the house, I found slit

marks across the entire ceiling, which suggests

the militiamen must have thrust their machetes

into the ceiling to try and stab anyone who may

been hiding in the roof.

East Timor’s spiritual leader, Bishop Carlos

Belo, said the death toll was 25, a figure he was

told by the local Indonesian military commander.

People I spoke to in Liquisa said the toll

was much higher, and by 2003, when a serious

crimes investigation finally took its investigation

to court, the figure was said to be up to 200 – no-

body knows for certain because the bodies were

taken away in a truck.

The court heard detailed testimony about how

the Besi Merah Putih militia held a ceremony

before the massacre in which each member was

allegedly forced to drink a cocktail of alcohol,

animal blood and drugs to prepare themselves

for the church killing.

Testimony implicated the direct participation

in the attacks by Indonesian soldiers, who were

allegedly dressed in civilian clothes to look like

militia members.

Some of East Timor’s most prominent pro In-

donesia militia figures, including Eurico Guterres

and João Tavares, were the primary suspects and

leading figures during the massacre.

The court heard from one eyewitness, Her-

minia Mendes, how the militia along with the

police and the military attacked the church.

“They fired shots into the air to give the signal

to the militia to enter the church, and then they

started shooting the people,” she told the court

in 2003.

“Wearing masks that covered their faces the

militia and the military then attacked with axes,

swords, knives, bombs and guns.

“The police shot my older brother, Felix, and

the militia slashed up my cousins, Domingos,

Emilio, and an eight-month old baby.”

Ms Mendes described how she desperately

tried to flee with others to the Carmelite convent.

“The militia, police and military had prepared

a truck to carry people to the district administra-

tor’s house,” she said.

“When we arrived the militia continued their

actions and continued beating and stabbing

civilians.

“After about three hours Augustinho (a civil

servant)… made an announcement to the people,

saying, ‘Go home and raise the Indonesian flag.

And tie it to your right hand to show that we are

all people who are prepared to die for this flag’.”

By the time David and I arrived in Liquisa we

found most houses in Liquisa were flying the red

and white flag of Indonesia.

People were petrified of another attack and

were flying these colours for protection.

As David and I walked the streets we saw

many strange and disturbing sights.

In one neighbourhood the air was filled with

smoke from piles of leaves burning in the gutters

– it gave the place an eerie, nightmarish look.

Youths loitered in the street watching us and

moving away.

They looked weary and drained of all spirit –

like zombies.

Many wore tattered red and white headbands,

or had red and white crepe paper wrapped

around their arms and bodies.

In any other circumstances they could have

been mistaken for football fans trailing home

after losing a big match.

But in Liquisa, after a massacre, they were

simply trying to avoid provoking further attack

from a crazed and unpredictable enemy.

It was still many months before East Timor’s

vote for independence and the pro-Jakarta militia

were doing everything they could to intimidate.

And where were the United Nations’ peace-

keepers in this chaotic situation?

It wasn’t until May 1999 – a month after the

Liquisa massacre - that East Timor’s former

colonial power, Portugal, signed agreement to

allow East Timorese to vote on their future.

That deal was endorsed by the UN and sig-

nalled the start of the UN’s participation in the

voting process.

Significantly, the UN allowed the Indonesian

police force to be in charge of security in the

lead up to the August ballot.

That proved a poor decision.

As well as more attacks and killings leading

up to the August ballot, violence erupted once a

majority of eligible East Timorese voters chose

independence from Indonesia.

Some 1400 civilians died.

About 250,000 people – more than a quarter of

the population fled to West Timor, where many

were housed in refugee camps.

Martial law was imposed.

The UN then sent in an authorised force

(INTERFET) – consisting mainly of Australian

Defence Force personnel – to restore order and

rebuild.

I returned to Liquisa a few years later.

A youth choir was singing in the church São

João de Brito.

Their voices were sweet and beautiful. Peace

had finally come.

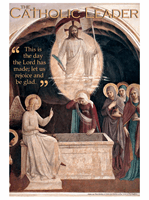

Destruction:

A burnt-out street in Dili East Timor, after pro-Indonesia militia gangs ran riot in 1999.

Journalist Mark

Bowling reflects on

a shocking event in

East Timor in 1999

Independence fighter:

East Timor guerrilla

leader and later president, Xanana Gusmao

meets with journalist Mark Bowling.