4

The Catholic Leader, April 22, 2018

www.catholicleader.com.auAnzac Day

By Emilie Ng

MATTRESS maker Private Frank

Percy Hanlon was waiting in the

trenches for his call of duty on a

railway line when a mortar shell ex-

ploded near him and another soldier.

Fellow soldiers wrote eyewitness reports

confirming the “rather slim and rather quiet”

20-year-old was killed “instantaneously” on

April 23, 1917, around 800 metres away from

Bullecourt, France, where days later emerged

one of the bloodiest battles the Australian army

had endured.

Private Hanlon had only turned 20 three months

earlier, enlisting in the army when he was only 19.

Private Victor Harry Carby was in the burial

party, and made a cross for his mate near where

Private Hanlon had died.

Within weeks that site was destroyed, as the

battle between the Australians and British Army

against the Germans that killed thousands of men

left nothing in the ground behind.

Though his body was never found again, he was

honoured at the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial.

Fr Edward Sarsfield Barry, a Catholic chaplain

to Australian soldiers and the first priest at Our

Lady of Victories Church, a war memorial in

Bowen Hills, notified one of Private Hanlon’s

nieces about the tragic death.

Almost one hundred years later, The Gap pa-

rishioner Tom Vanderbyl jumped on the Internet

and discovered letters pinpointing the precise

location where his great-uncle, Private FP Hanlon,

had died.

“We got a fair bit of stuff from the web;

there’s a great access to great materials now and

resources online,” Mr Vanderbyl said.

“If you know the name of the person you’re

connected to and you list it in the search, there’s a

lot of websites and resources available to you.

“That’s all we really did, once we became inter-

ested, we just started to research online.”

Among the official documents detailing Private

Hanlon’s deployment, which began in Egypt and

ended in Bullecourt, were letters from his “friends

in the trenches” who reported where and how he

died.

After contacting the National Archives of

Australia in Canberra, Mr Vanderbyl learnt the

digitised documents accessible online were just

the tip of the iceberg.

“There was a mud map attached to one of these

letters, drawn by one of his comrades, and it

Internet reunites

lost soldier with

descendants

nearly 100 years

after his death

Online discovery awakens Anzac spirit

shows exactly where it was,” Mr Vanderbyl said.

The mud map was not available online, but

Mr Vanderbyl obtained a hardcopy of it from the

Archives.

“I took that mud map and took up a Google

Maps of the whole area,” he said.

“He was basically blown up next to an old

railway line, and this no longer exists, but when

you look at Google Maps you can still see the

location of a railway line just by the trees and

different colours.

“So I was sort of measuring it out on the

Google maps, based on the information that’s in

these documents, and we were able to pin-point

just about where it happened.”

But it wasn’t enough to see the site on the

computer – Mr Vanderbyl decided to tack on a

side trip to Bullecourt during a family vacation

to Europe.

“When we were going on a trip to Europe to

visit family and friends … we thought we’d take

a side trip to go to the place where Frank Percy

Hanlon was killed just to get a sense of it,” he

said.

“You go to Anzac Day parades and Anzac

Day commemorations but we never actually con-

nected more directly than that.

“We were interested to do that, to go and see if

we can find out and visit where it was.”

In December 2015, the Vanderbyl family

drove within metres of the site that took the life

of his great-uncle 100 years ago this year.

The thick mud – which Mr Vanderbyl said ran

three metres deep – kept the family from stand-

ing on the actual site of Private Hanlon’s death.

“Not traversable even by a car like that,” Mr

Vanderbyl said, pointing to a photo of his family

in the car just metres from the special site.

“That’s as close as we could get because of

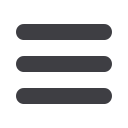

Anzac remembrance:

Tom and Saskia Vanderbyl and their three sons Oliver (then 15), Jeremy (then 11), Ben (then 17) outside the Villers-Breton-

neux Memorial in 2015. The family travelled to northern France to locate the site where Mr Vanderbyl’s great-uncle was killed in Bullecourt during

the First World War.

Photo: Tom Vanderbyl

Family moment:

In December

2015, the Vanderbyl family

drove within metres of the

site where Tom Vanderbyl’s

great-uncle 100 years ago this

year. The thick mud kept the

family from standing on the

actual site of Private Hanlon’s

death. The site is the top left

of the photo.

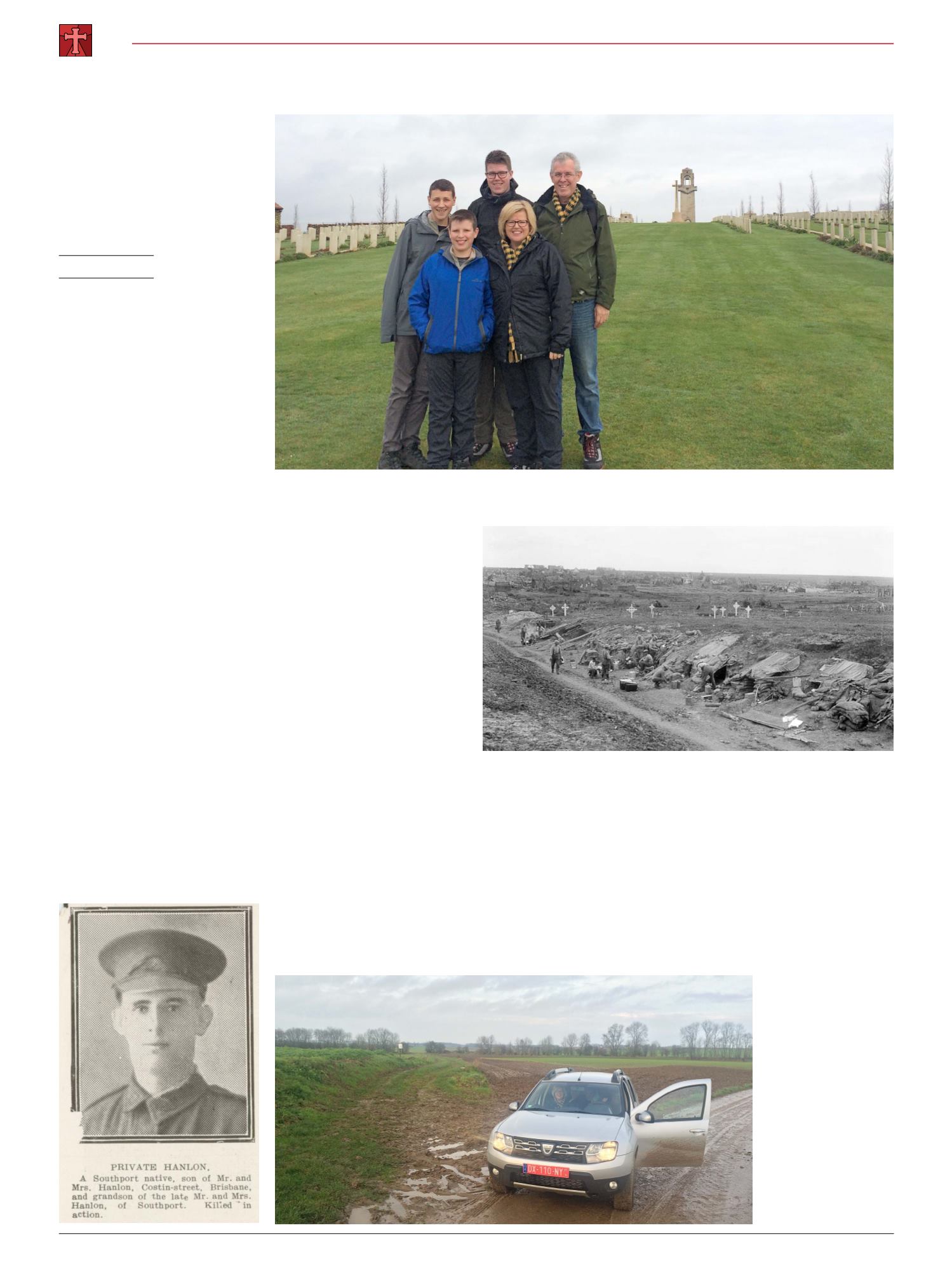

Heavy casualties:

Troops billeted in a sunken road near Bullecourt on May 19, 1917

that mud (which) you hear about it in Anzac

stories.

“We stopped both this side and on the other

side, we stopped there and we were about to get

out and walk; we were approached by a local

farmer, he told us that was a not a good idea.”

The Vanderbyl’s oldest son, Ben, was 17 at

the time, just two years younger than when his

great-great uncle enlisted in the First World

War.

“Imagine being out here doing this?” Mr

Vanderbyl said.

“His mother, Sarah Hanlon, who must have

been my great-grandmother, she never really got

over his death.

“There was a letter, of which the first page is

online, the rest must be in the files in Canberra,

where you get the sense she hadn’t got over it

years later.

“You can see the anguish come through in her

letters back and forth with the war office, trying

to get more information.

“Obviously, he had the world in front of him.”

While in Bullecourt, Mr Vanderbyl said he

could sense the appreciation the French of that

town had for the Australians.

“They still have a special place for Austral-

ians,” Mr Vanderbyl said.

“You just feel how much appreciation there

is for the Anzac’s effort and the importance the

Australians had at the time in terms of their

action.”